One Hundred and Forty plus years ago, a group of concerned citizens recognized that work animals were being treated inhumanely and unjustly. Following in the footsteps the New Hampshire State Legislature which enacted humane laws to protect “dumb animals”, the Portsmouth Society to Prevent Cruelty to Animals was formed in 1872. The organization was incorporated and the following year the name was changed to the New Hampshire Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals—one of the first ten such societies established in the United States.

Today, the Society maintains its central mission of prevention of cruelty to animals through investigations and it continues to work to improve legislation as it affects animals. In addition, programs have been expanded to include animal sheltering and adoption, humane education, lost and found services, spay and neutering of shelter pets, behavior and training, youth programs and more.

A Brief History of the Animal Protection Movement and the Road to New Hampshire, by Leslie Schwartz

In the wake of the Emancipation Proclamation, the Civil War, and a steady growth in American Evangelism, the animal protection movement was founded in the United States. Like many Northern influences that made their way south of the Mason-Dixon Line, animal protectionism arrived on American shores in a carpetbag, in this case, a direct import from England.

The movement had begun in that country close to fifty years before, as early nineteenth-century Britons witnessed their respective abolition of slavery (1807), religious enthusiasm, reaction to the Industrial Revolution, and new ideas about the concept and distribution of “property”. Thus, post-Civil War America and Britain in the early 1800’s were characterized by many of the same phenomena, explaining the lapse in time between the birth of the movement there and here. Widening humanitarian inroads paved the way for animal welfare on both sides of the Atlantic, only at different “ripe” times.

America, along with its British counterpart, also experienced a growing Victorian sentimentalism toward home and hearth, family and farm. Children and pets were lavished with endearment, seen as bringing joy to humanity through nothing other but their very “innocence.” For many such notions extended easily from domestic pets to domesticated work animals, whose existence and well-being enhanced human comfort and family life both emotionally and commercially. It was upon these animals that daily activities depended, and it is therefore no surprise that the first legislative efforts in Anglo-American animal protectionism centered upon the welfare of cows and horses.

The carpetbag that landed in the United States containing the British prototype for an animal’s protectionist organization was carried by a New York aristocrat and former American consul in Russia named Henry Bergh. Bergh had visited England, where he learned of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) and its accomplishments. In turn, he founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) in his home state in 1866, with the help of such notables as John Jacob Astor and Horace Greeley. The latter was editor of the liberal New York Tribune and would run against Ulysses Grant in the presidential election of ’72. Bergh’s agency worked to enact anti-cruelty legislation and functioned as a means by which subsequent enforcement of such laws might be secured.

Just as Bergh’s ASPCA emulated the RSPCA, the former agency would itself be emulated thereafter. Organizations of the like-kind would emerge around the country. Among the earliest of these cropped up in Philadelphia (1867), San Francisco and Massachusetts (both in 1868). The Massachusetts society, in particular, laid major groundwork locally and beyond. Its founder, George Thorndike Angell, is remembered as the father of animal protection for all New England. In contrast to Henry Bergh, Angell was a self-made man, a lawyer with countrified beginnings. He invented the concept of “humane education,” a program designed to change peoples’ ideas and practices with regard to animals. Believing this to be the best method of cruelty prevention, he created the American Humane Education Association. It is due, no doubt, to Angell’s preeminence that another society would soon be established in a state bordering on Massachusetts…New Hampshire.

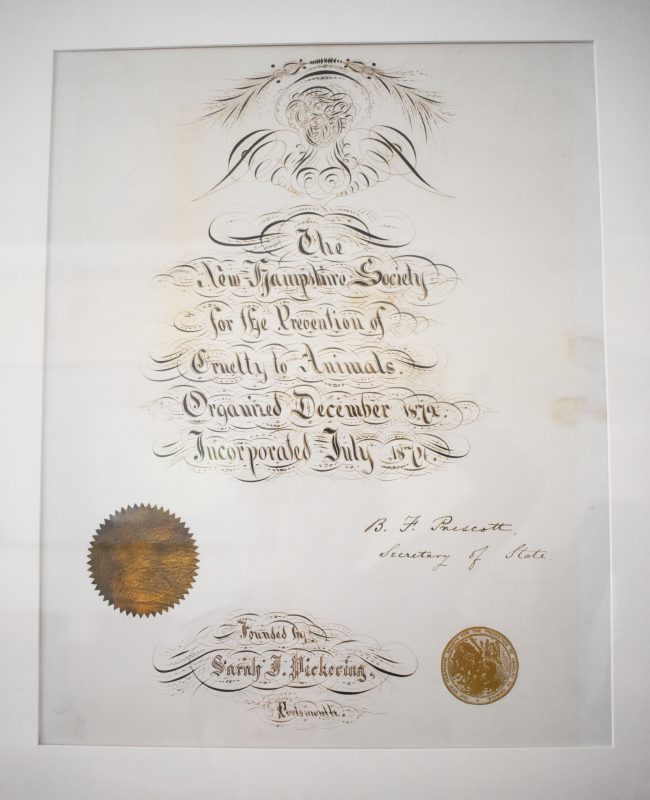

In 1872, one of the first ten SPCAs in the nation was founded in Portsmouth. In 1874, it was incorporated by the state, and in 1875 the name was changed to “The New Hampshire” SPCA by petition to the legislature. Where most other such agencies were established in metropolises, it seems curious that one would emerge here. Looking at the founders, however, provides some insight; their profiles reflect much of that which characterized animal protectionists and other humanitarians on the whole.

The party most responsible for the establishment of the Portsmouth Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in 1872 was a woman named Sarah Pickering. Mrs. Pickering was a daughter of the Jenness family, acquiring the new last name through her marriage to prominent merchant and banker John Jacob Pickering. She served as president of the society until 1878, and as a director until her death in 1888. It was her intention to create an agency by which an 1870 law enacted in New Hampshire to protect dumb (i.e. helpless) animals might be enforced. As the Pickering’s were childless in a family-centered world, it is easy to see how a woman of leisure such as she would feel compelled to devote herself to another area of emotional and legal responsibility.

Two additional women joined Mrs. Pickering in her endeavor: Elizabeth Pearson, unmarried at the time, and Margaret Haven, wife of Portsmouth counselor-at-law Alfred Haven. The three remaining co-founders were men. One was none other than the Honorable Ichabod Goodwin, former Governor of New Hampshire, State Senator and retired shipping merchant. A Whig-to-Republican, Goodwin was renowned for his Unitarian insistence on religious toleration; he presided over numerous benevolent organizations as well. (His life and works truly contradicted his name; ironically “Ichabod” means “without honor.”) Another was William H. Y. Hackett, president of the First National Bank of Portsmouth and a counselor-at-law. Finally, US Congressman Capt. Daniel Marcy (as in Marcy Street) lent his name to the fledgling society.

Of the six founders, Marcy is perhaps the most colorful and controversial. A life-long Democrat, Marcy supported the concept of ending the Civil War even if it meant the continuance of slavery. Otherwise celebrated for his generosity and humanitarian spirit, Marcy proves an interesting anomaly when viewed with regard to animal protectionist in general. While the movement both in Britain and America typically drew individuals from diverse political orientations, ethno-religious backgrounds, and either gender, there had traditionally been a strong conceptual connection between the cruelty of slavery and cruelty to animals. Many of the same people who embraced animal protectionist ideals declared themselves abolitionists as well.

The relationship between the problem of slavery and animal concerns is evident in two other (and familiar) names appearing in the early NHSPCA records: Ladd and Hale. A member of a committed abolitionist family, served as an officer of the NHSPCA. His father was also the founder of the American Peace Society. Mrs. Hale, a society director, was the widow of the late John Parker Hale of Dover. Born in Rochester, Hale is remembered as one of the most outstanding litigators in New Hampshire history. He too, was a dedicated abolitionist, running in 1852 as the Free-Soil Party candidate for President. Mrs. Hale carried on his legacy of humanitarianism after his death.

Since the early days of the NHSPCA, the animal protectionist movement in its broadest sense has evolved in many ways. One way we may see change is in noting how much wider the circle has become in terms of the types of animals that are now protected. For example, the husband of primary founder Sarah Pickering had once dabbled in the whale-oil business. By today’s standards, this kind of venture would be considered unconscionable and inconsistent with animal protectionist agendas. Yet it was individuals such as Sarah whose thoughts and activities initiated a process, the comprehensive legislation on behalf of our friends, the animals.

QUOTES:

“A deacon in good standing in a country church, overloaded an old horse which formerly belonged to an ex-Governor of this state, until the animal became balky, and [he] then beat him with iron trace chains until great ridges were raised on his sides and legs, then ground his ears between two stones and finally filled the horse’s bleeding ears with rough gravel and stones and tied them down to his head with a long strip of cloth. The deacon was prosecuted…but was not indicted.” President’s Report, NHSPCA 1880

“One day last September an anonymous complaint was made that a poor horse had been driven from this city to Newington in a very cruel manner. Two of our officers upon this meager information, started immediately for Newington to investigate. I can give no adequate description of [the horse’s] condition. The hide was beaten off his ribs on both sides, his on both sides, his shoulders, neck and back were raw with harness galls. The case was brought immediately to trial and the jury returned a verdict of guilty. The fellow is now serving a term of imprisonment in jail.” Annual Report of the NHSPCA 1880

“We regret to report that several dogs have been poisoned, probably deliberately, by offenders who have escaped detention.” Annual Report of the NHSPCA 1940

“WHEB, through reporter Charles Gray, has been of invaluable assistance to us in finding the owners of strays and many dogs are returned each year.” Annual Report of the NHSPCA 1946

This special fund …is conditioned, by her will, on our NHSPCA continuing in existence. We can assure the public that this New Hampshire Society will continue to exist and flourish.” Annual Report of the NHSPCA 1946

“This is our first post-war report and, in fact, the first full report we have made since the United States was suddenly plunged in the Second World War. Nevertheless, we have continued to do our work constantly and effectively along the lines or our trusts which were created for the protection of animals and children.” From the Address of the President. Annual Report of the NHSPCA 194

“As we interpret the scope of our service to the public it is to be the ‘eyes and ears’ of the public, to be on the alert to see and hear instances of cruelty to animals, and to ask for their discontinuance, or to draw to them the official attention of the criminal authorities of the counties and the state. In cases where necessary we may well become the complainant in the criminal prosecution. We are not to encroach upon any of duties of any official or public prosecutor but may consult with, and aid them, and that is what we are constantly doing.” State Agent’s Report from the Annual Report of the NHSPCA 1939